About the DeSoto County Historical Society

The DeSoto County Historical Society is an all-volunteer, not-for-profit organization dedicated to preserving and promoting the history of DeSoto County for future generations.

A restored, late-nineteenth century home, the John Morgan Ingraham House Museum, 300 N. Monroe Avenue, Arcadia, is a memorial to all early pioneer families of the City of Arcadia and DeSoto County. It showcases a simple kind of “Florida Cracker” architecture and lifestyle and includes furniture and artifacts from that period, as well as exhibits about the area’s history. The Museum is open from 9 a.m. to 1 p.m. on Thursdays and from 9 a.m. to 1 p.m. on the second and fourth Saturdays of the month. Tours are free, but donations are welcomed and appreciated!

The Howard and Velma Melton Historical Research Library is located in the adjacent John Morgan Ingraham Seed House, 120 W. Whidden Street, Arcadia. The Research Library includes historic photographs, newspaper articles, letters, receipts, family histories, and many other documents. Research assistance is available.

BECOME A MEMBER

As a member you will receive a monthly newsletter inviting you to our programs and events, our monthly meetings, Pioneer Day festival on the fourth Saturday in March, and more. Click Here for Membership Application

DeSoto County Historical Society’s Board of Directors, 2024

Adrian H. Cline, President

Vernon Keen, Vice-President

René Collins, Secretary

Nancy “Eric” Erickson, Treasurer

Carol Mahler, Museum and Research Library Coordinator

Ruth Dunn, Director

Jeff Griffis, Director

Ellen Hutson, Director

Stella Parker, Director

Luke Wilson, Director

Norma Banas, Past President

The Tree of Knowledge

Arcadia’s Oak Named “The Tree of Knowledge”

by Carol Mahler

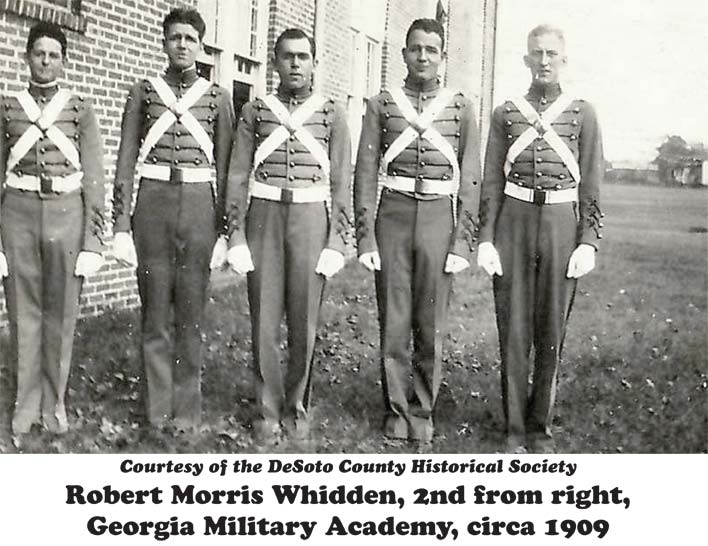

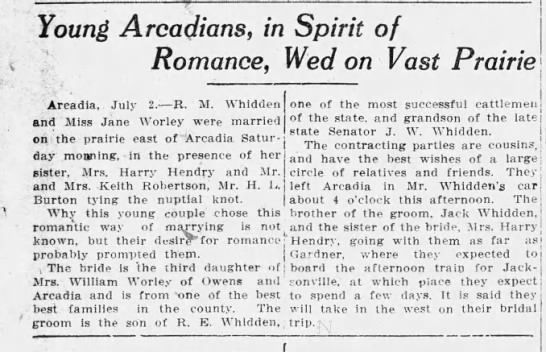

The DeSoto County Historical Society’s logo features the “Tree of Knowledge” in downtown Arcadia, the focal point of a city park established in 2002. The live oak was planted as a ten-year-old sapling in 1938 by the newly formed Arcadia Garden Club. It replaced the original two trees planted in 1889 to celebrate the births of Robert Morris Whidden (2nd from right) (1889-1927) and Inez Carlton Taylor (left side) (1889-1957).

As early as 1928, the oak was known as “The Tree of Knowledge” because politicians spoke beneath its shade. The March 1, 1928 Arcadian advertised that “Doyle E. Carlton, candidate for governor, will speak in Arcadia, Saturday Night, . . . under ‘Tree of Knowledge’.”

When the tree was replanted in 1938, people questioned the origin of the name, and one answer was published in the Feb. 5, 1938, Tampa Tribune, “The tree received its name, ‘The Tree of Knowledge’ from the late Uncle Jim Hollingsworth. As a member of the city council in 1900, he conceived the idea of placing benches under the tree as a city gathering place.” In later years, many people told stories and tall tales sitting in the tree’s shade, so the name was used derisively.

Elected in 1971 as Arcadia’s first African-American city council member, Eugene Hickson, Sr., grew up during the same years as that oak matured and graduated from the segregated Smith-Brown School in 1948.

He must have been familiar with oak’s history when he served his first term as Arcadia’s mayor (1979-1984). On Dec. 19, 1981, under the Tree of Knowledge, he and the Reverend Fred Spencer, pastor of Trinity United Methodist Church, held a prayer service for the safe release of U.S. Army Brigadier General James “Jimmy” Dozier after he had been kidnapped by terrorists in Italy two days previously. The two even tied a yellow ribbon around the tree as the song “Tie A Yellow Ribbon Round The Ole Oak Tree” by Tony Orlando and Dawn was popular at the time.

Property Appraiser David A. Williams speculated that the misconception that the Tree of Knowledge was used as a “hanging tree” may have arisen from the tradition of the “political graveyard.” After an election, wooden tombstones for the losers were placed in the nearby grass, and some candidates may have been “hanged in effigy.” Such over zealousness ended the practice.